Brigantes study group

Brigantes

What do we know about the Brigantes?

The Brigantes were a pre-literate society. The sparse written references to them, were by Greeks and Romans such as Ptolemy and Tacitus in his Annals and Histories. A number of volumes of the Annals, dealing with key years and which may have told us more about the Brigantes, were lost.

WHO. The Brigantes were a Celtic tribe. Ptolemy lists the Brigantes also as a tribe in Ireland, where they could be found around Wexford, Kilkenny and Waterford while another probably Celtic tribe named Brigantii is mentioned by Strabo as a sub-tribe of the Vindelici in the region of the Alps.

The name Brigantes could have derived from the Goddess Brigantia whom they are thought to have worshipped. It could also have derived from the Celtic word “briga” meaning hill, so Brigantes could have meant dwellers in high places or high as in powerful people. Cartimandua was described by Tacitus as being “of powerful lineage” There is some speculation that her predecessors may have formed links with Julius Caesar after his first invasion in 55/54 BC. A small number of unusual, high status gifts were recovered at Stanwick and are thought to be as early as 45 BCE

The Brigantes are thought to have been the largest and most powerful tribal group in the area. A number of smaller tribes lived through out the territory and formed a loose federation ruled by the Brigantes. It is not clear if this was the real situation or a Roman construct imposed on the area. Cartimandua became a “client” of the Roman empire and is thought to have been among the dozen or so native rulers who gave allegiance to Claudius in AD 43, consequently her lands formed a buffer between Roman occupied southern Britain and the northern Britain of the Picts. Some Archaeologists suggest that the Romans did not prioritize imposing direct rule in this area because there were fewer natural resources to exploit.

Whatever the reasons, between AD 43 and 69/70 the Brigantes ruled the area backed up by Roman power when needed. It seems to be the case that there were pockets of good arable land in the area of the Brigantes but there is little evidence that significant surplus food was grown. In the south of the country the Romans were able to live off the land by purchase or requisition of surplus grain. When the army, finally moved north, at least initially, grain had to be imported by sea, to ports along the east coast.

Research underway at Whirlow Hall Farm in Sheffield may cast more light on this supposition..

A few coins have been found in the area but they were not thought to be minted by the Brigantes. The recent find at Scotch Corner of 1300coin mould trays may change this view but the excavation report is not yet available. See British Archaeology May /June 2017

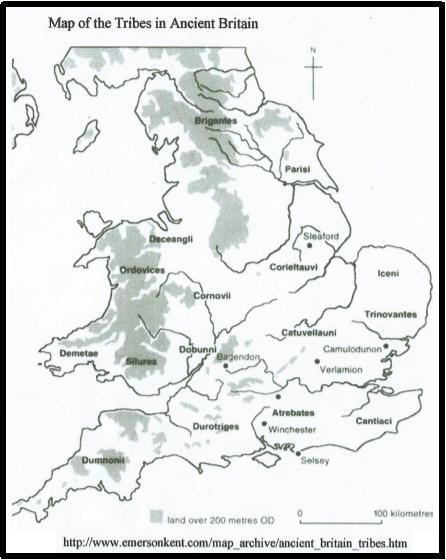

Where They occupied a region roughly north of Derby/Sheffield /Doncaster ( the southern border may have varied over time but been around the River Don) and south of present day Scotland. It is thought that the building of Hadrian’s Wall in 122AD divided Brigantian communities.

According to Ptolemy, the territory stretched from “sea to sea” although the Parisi, who are not thought to have been part of any Brigantes federation, occupied the area around the Humber estuary.

Ptolemy listed a number of “cities of the Brigantes” some of which have been identified. The location of their “capital” is not confirmed and several places have a possible claim, but the fortified enclosure at Stanwick near Darlington was one of their significant power bases. This site was excavated by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in the early 1950s and again in the late 1980’s by Colin Haselgrove, Peter Turnbull and Leon Fitts. They came to very different conclusions about the history of the development of the site and Colin Haselgrove’s theory is currently, thought to be more likely.

Stanwick - Oppidum

Stanwick has been described variously as “perhaps the most important native site in northern England” and a.. “unique oppidum site (Ross 2011)

And “as easily the most extensive and impressive surviving iron age monument in northern England

( Haselgrove 1990)

The site is a few miles from Darlington a couple of miles north -west of Scotch Corner on the A1

It has an 8km perimeter earthwork which survives at a height of 5m in some places. The scale of effort to build the site indicates that it must have had more than purely local significance to be able to call on the human power necessary for the construction.

The site lies close to two major route ways which predate what were to become the Roman roads of Dere Street and the Stainmore Pass

The earthworks enclose 300 hectares ( 741 acres) of well drained land including two streams, the Mary Wild Beck and the Aldborough Beck

The areas excavated so far show several phases of building work on the site. Later constructions seemed designed to separate public from private spaces and may indicate the decision of an elite group for privacy. Excavation of the entrance way revealed “an imposing stone –revetted structure. When standing the entrance must have presented an impressive sight to visitors”

( Haselgrove 1990)

The surrounding land is one of the few areas in north-east England classed as Grade 2 in the Agricultural Land Classification and would have been an excellent resource for both arable and pastoral farming ( Ross 2011)

“Carbonised remains of spelt wheat and 6 row barley, numerous rotary querns and abundant faunal assemblage indicate a thriving mixed economy not the primarily pastoral as existence envisaged by Wheeler. “( Haselgrove 1990)

There is also some evidence for metal working on the site. One of the five inhumations excavated was of a female buried with metal working equipment.

Finds

“Local Coarse wares, brooches and ornaments... Iron Age and Roman coin, glass drinking vessels, pottery, Mediterranean wine and oil amphorae. Many of these imports are extremely unusual, rare Samian forms. The rarity if some of the materials such as volcanic glass indicate that these were possibly diplomatic gifts rather than the result of general import or normal trade.

Interestingly , most date from the period between the Claudian conquest and AD 70. The imports mark out Stanwick as a settlement of unusual distinction . The dates support the theory that Cartimandua received tangible benefits from her position as client Queen.

Other finds pre-date AD43 and support the notion of some level of “diplomatic relations” between the elite of Stanwick and Rome. Some possibly dating back to the initial invasion by Julius Caesar in BCE 55/54 and possibly account for the comment that Cartimandua was of “powerful lineage”.

Wheeler’s excavation also uncovered various finds described as “spectacular” including a sword with a wooden scabbard and a human skull which may originally have adorned the gateway.

Haselgrove, found 5 adult burials placed on or close to boundaries. One of the male adults had been buried with a six month old. He felt that these hinted at complex rituals.

What happened to Stanwick?

Why after the huge amount of effort which was expended to create such an important centre, did it fall into disuse?

There are several theories. One thought is that Stanwick was primarily a site devoted to the display of power and the standing of the elite. It was abandoned around AD 70 when the Brigantes under the leadership of Venutius, rebelled , and Cartimandua was rescued by Roman Auxiliaries.

Defence was not uppermost in the design of Stanwick so when circumstances changed it was not an appropriate rebel stronghold. Certainly excavations to date have not revealed any evidence that the earthworks were “slighted” by the Romans: which would be expected if any serious fighting took place there.

If it had been a major Brigantian centre why didn’t the Romans use it for the civitas?

Possibly it was not in a strategically attractive position for Roman administration for the area. Isurium Brigantia when it was established in late 1st Century or early 2nd century (AD) was at Aldborough relatively close to York and on the Roman road, Dere Street running between Eboracum and the Antonine Wall.

An interesting footnote to Stanwick has been suggested by Jennifer Proctor (CA Dec. 2012)

She excavated Faverdale which lies 10km NE of Stanwick , between the Roman roads of Dere Street and Cade Road. It is not certain when the Faverdale site was first established but “with its Round Houses, enclosure and ditches it was built in the indigenous rather than the Roman style, and from AD 70 “ the inhabitants were able to access Roman objects on a scale unimaginable ( in this area) even a generation before” She suggests that possibly some of the inhabitants with their goods relocated to Faverdale when Stanwick was abandoned.

Wheeler argued that Stanwick was a stronghold of the rebel consort Venutius and that various substantial earth works were built to fortify the site against Roman attack. Haselgrove argues that the low earthwork perimeter of almost 6 miles would have been indefensible. He suggests that the large enclosure indicates the need to contain cattle and/ or horses and most likely dates to the period when Queen Cartimandua was secure. However the low earthworks would have provided a barrier to Roman Cavalry attack( Haselgrove 2013) The later additions of internal fortifications are now thought to be evidence of the differentiation of elite areas to separate them from the majority of residents at Stanwick .

What happened?

There are two internal rebellions reported by Tacitus although he may have muddled or duplicated events. In the first in AD 48, rebels possibly led or encouraged by Venutius the Queen's consort, were defeated by Roman troops and Queen Cartimandua was restored by the Romans. At this point she is thought to have taken Venutius’ brother and some other kinsmen as hostages against his future good behaviour. In AD 51 Cartimandua handed Caratacus over to the Romans and sealed her “client” status. “The man himself (Caratacus) had sought sanctuary with Cartimandua, queen of the Brigantes, ( but adversity is generally unsafe) he was chained and handed over to the conquerors... in the ninth year after the war in Britain began.” . Tacitus Annals

The later rebellion thought to have followed the divorce of Cartimandua and Venutius and her subsequent marriage to Vellocatus, is reported at around 69 AD. This time Roman soldiers were not available and the battle between Brigantians and a Roman Auxiliary troop resulted in the Queen being rescued but the rebellion not suppressed. “our auxiliaries both horse and foot, then fought several engagements with varying success, but eventually rescued the queen. The kingdom was left in Venutius’ hands – and the war in ours” Tacitus Annals

Venutius was finally defeated in AD 73 by Petillius Cerialis, Govenor of Britain since 71 the Romans established an administrative civitas for the management of the native population at a site a several miles south of Stanwick which they called Isurium Brigantium (Aldborough near Ripon) This site has recently been the subject of a survey by Martin Millett and Rose Ferriby of Cambridge University. See also recent research and excavation at Faverdale ( 10 k west of Stanwick) , which has been suggested as the settlement developed by defeated Brigantians displaced by the fall of Stanwick.

So did the Brigantes rule a federation of smaller tribes across a large swathe of the north of the country?

The more likely scenario is that between AD 43 and AD 69 under Queen Cartimandua, the Brigantes were the largest tribal group in the area and they were recognised and their power bolstered by Rome partly for ease of administration, such as collection of taxes in slaves , hunting dogs etc. and partly as a buffer state against north Britain. When the tribe rebelled and the Queen was displaced Vespasian decided to conquer the whole area and impose direct rule.

As far as we can tell, nothing further was heard of the Brigantes throughout the Roman occupation.

There is at least one indirect reference in the Vindolanda writing tablets. Vindolanda was originally established as a fort on the Stanegate which linked present day Newcastle and Carlisle in the mid 80’s AD. Local inhabitants around the fort are referred to in one letter as “wretched little Brits”. As these people were almost certainly Brigantian the reference gives some idea of the way some Romans thought about the local people.

Research updated July 2017

Haselgrove, C. C . et al “Stanwick-Oppidum” Current Archaeology 119 1990c pp 380 -385

Ross, C. M. Tribal Territories from the Humber to the Tyne BAR British Series 540 2011

Proctor, J “ Roman Faverdale” Current Archaeology 273 Dec. 2012 pp 20-25

What do we know about the Brigantes?

The Brigantes were a pre-literate society. The sparse written references to them, were by Greeks and Romans such as Ptolemy and Tacitus in his Annals and Histories. A number of volumes of the Annals, dealing with key years and which may have told us more about the Brigantes, were lost.

WHO. The Brigantes were a Celtic tribe. Ptolemy lists the Brigantes also as a tribe in Ireland, where they could be found around Wexford, Kilkenny and Waterford while another probably Celtic tribe named Brigantii is mentioned by Strabo as a sub-tribe of the Vindelici in the region of the Alps.

The name Brigantes could have derived from the Goddess Brigantia whom they are thought to have worshipped. It could also have derived from the Celtic word “briga” meaning hill, so Brigantes could have meant dwellers in high places or high as in powerful people. Cartimandua was described by Tacitus as being “of powerful lineage” There is some speculation that her predecessors may have formed links with Julius Caesar after his first invasion in 55/54 BC. A small number of unusual, high status gifts were recovered at Stanwick and are thought to be as early as 45 BCE

The Brigantes are thought to have been the largest and most powerful tribal group in the area. A number of smaller tribes lived through out the territory and formed a loose federation ruled by the Brigantes. It is not clear if this was the real situation or a Roman construct imposed on the area. Cartimandua became a “client” of the Roman empire and is thought to have been among the dozen or so native rulers who gave allegiance to Claudius in AD 43, consequently her lands formed a buffer between Roman occupied southern Britain and the northern Britain of the Picts. Some Archaeologists suggest that the Romans did not prioritize imposing direct rule in this area because there were fewer natural resources to exploit.

Whatever the reasons, between AD 43 and 69/70 the Brigantes ruled the area backed up by Roman power when needed. It seems to be the case that there were pockets of good arable land in the area of the Brigantes but there is little evidence that significant surplus food was grown. In the south of the country the Romans were able to live off the land by purchase or requisition of surplus grain. When the army, finally moved north, at least initially, grain had to be imported by sea, to ports along the east coast.

Research underway at Whirlow Hall Farm in Sheffield may cast more light on this supposition..

A few coins have been found in the area but they were not thought to be minted by the Brigantes. The recent find at Scotch Corner of 1300coin mould trays may change this view but the excavation report is not yet available. See British Archaeology May /June 2017

Where They occupied a region roughly north of Derby/Sheffield /Doncaster ( the southern border may have varied over time but been around the River Don) and south of present day Scotland. It is thought that the building of Hadrian’s Wall in 122AD divided Brigantian communities.

According to Ptolemy, the territory stretched from “sea to sea” although the Parisi, who are not thought to have been part of any Brigantes federation, occupied the area around the Humber estuary.

Ptolemy listed a number of “cities of the Brigantes” some of which have been identified. The location of their “capital” is not confirmed and several places have a possible claim, but the fortified enclosure at Stanwick near Darlington was one of their significant power bases. This site was excavated by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in the early 1950s and again in the late 1980’s by Colin Haselgrove, Peter Turnbull and Leon Fitts. They came to very different conclusions about the history of the development of the site and Colin Haselgrove’s theory is currently, thought to be more likely.

Stanwick - Oppidum

Stanwick has been described variously as “perhaps the most important native site in northern England” and a.. “unique oppidum site (Ross 2011)

And “as easily the most extensive and impressive surviving iron age monument in northern England

( Haselgrove 1990)

The site is a few miles from Darlington a couple of miles north -west of Scotch Corner on the A1

It has an 8km perimeter earthwork which survives at a height of 5m in some places. The scale of effort to build the site indicates that it must have had more than purely local significance to be able to call on the human power necessary for the construction.

The site lies close to two major route ways which predate what were to become the Roman roads of Dere Street and the Stainmore Pass

The earthworks enclose 300 hectares ( 741 acres) of well drained land including two streams, the Mary Wild Beck and the Aldborough Beck

The areas excavated so far show several phases of building work on the site. Later constructions seemed designed to separate public from private spaces and may indicate the decision of an elite group for privacy. Excavation of the entrance way revealed “an imposing stone –revetted structure. When standing the entrance must have presented an impressive sight to visitors”

( Haselgrove 1990)

The surrounding land is one of the few areas in north-east England classed as Grade 2 in the Agricultural Land Classification and would have been an excellent resource for both arable and pastoral farming ( Ross 2011)

“Carbonised remains of spelt wheat and 6 row barley, numerous rotary querns and abundant faunal assemblage indicate a thriving mixed economy not the primarily pastoral as existence envisaged by Wheeler. “( Haselgrove 1990)

There is also some evidence for metal working on the site. One of the five inhumations excavated was of a female buried with metal working equipment.

Finds

“Local Coarse wares, brooches and ornaments... Iron Age and Roman coin, glass drinking vessels, pottery, Mediterranean wine and oil amphorae. Many of these imports are extremely unusual, rare Samian forms. The rarity if some of the materials such as volcanic glass indicate that these were possibly diplomatic gifts rather than the result of general import or normal trade.

Interestingly , most date from the period between the Claudian conquest and AD 70. The imports mark out Stanwick as a settlement of unusual distinction . The dates support the theory that Cartimandua received tangible benefits from her position as client Queen.

Other finds pre-date AD43 and support the notion of some level of “diplomatic relations” between the elite of Stanwick and Rome. Some possibly dating back to the initial invasion by Julius Caesar in BCE 55/54 and possibly account for the comment that Cartimandua was of “powerful lineage”.

Wheeler’s excavation also uncovered various finds described as “spectacular” including a sword with a wooden scabbard and a human skull which may originally have adorned the gateway.

Haselgrove, found 5 adult burials placed on or close to boundaries. One of the male adults had been buried with a six month old. He felt that these hinted at complex rituals.

What happened to Stanwick?

Why after the huge amount of effort which was expended to create such an important centre, did it fall into disuse?

There are several theories. One thought is that Stanwick was primarily a site devoted to the display of power and the standing of the elite. It was abandoned around AD 70 when the Brigantes under the leadership of Venutius, rebelled , and Cartimandua was rescued by Roman Auxiliaries.

Defence was not uppermost in the design of Stanwick so when circumstances changed it was not an appropriate rebel stronghold. Certainly excavations to date have not revealed any evidence that the earthworks were “slighted” by the Romans: which would be expected if any serious fighting took place there.

If it had been a major Brigantian centre why didn’t the Romans use it for the civitas?

Possibly it was not in a strategically attractive position for Roman administration for the area. Isurium Brigantia when it was established in late 1st Century or early 2nd century (AD) was at Aldborough relatively close to York and on the Roman road, Dere Street running between Eboracum and the Antonine Wall.

An interesting footnote to Stanwick has been suggested by Jennifer Proctor (CA Dec. 2012)

She excavated Faverdale which lies 10km NE of Stanwick , between the Roman roads of Dere Street and Cade Road. It is not certain when the Faverdale site was first established but “with its Round Houses, enclosure and ditches it was built in the indigenous rather than the Roman style, and from AD 70 “ the inhabitants were able to access Roman objects on a scale unimaginable ( in this area) even a generation before” She suggests that possibly some of the inhabitants with their goods relocated to Faverdale when Stanwick was abandoned.

Wheeler argued that Stanwick was a stronghold of the rebel consort Venutius and that various substantial earth works were built to fortify the site against Roman attack. Haselgrove argues that the low earthwork perimeter of almost 6 miles would have been indefensible. He suggests that the large enclosure indicates the need to contain cattle and/ or horses and most likely dates to the period when Queen Cartimandua was secure. However the low earthworks would have provided a barrier to Roman Cavalry attack( Haselgrove 2013) The later additions of internal fortifications are now thought to be evidence of the differentiation of elite areas to separate them from the majority of residents at Stanwick .

What happened?

There are two internal rebellions reported by Tacitus although he may have muddled or duplicated events. In the first in AD 48, rebels possibly led or encouraged by Venutius the Queen's consort, were defeated by Roman troops and Queen Cartimandua was restored by the Romans. At this point she is thought to have taken Venutius’ brother and some other kinsmen as hostages against his future good behaviour. In AD 51 Cartimandua handed Caratacus over to the Romans and sealed her “client” status. “The man himself (Caratacus) had sought sanctuary with Cartimandua, queen of the Brigantes, ( but adversity is generally unsafe) he was chained and handed over to the conquerors... in the ninth year after the war in Britain began.” . Tacitus Annals

The later rebellion thought to have followed the divorce of Cartimandua and Venutius and her subsequent marriage to Vellocatus, is reported at around 69 AD. This time Roman soldiers were not available and the battle between Brigantians and a Roman Auxiliary troop resulted in the Queen being rescued but the rebellion not suppressed. “our auxiliaries both horse and foot, then fought several engagements with varying success, but eventually rescued the queen. The kingdom was left in Venutius’ hands – and the war in ours” Tacitus Annals

Venutius was finally defeated in AD 73 by Petillius Cerialis, Govenor of Britain since 71 the Romans established an administrative civitas for the management of the native population at a site a several miles south of Stanwick which they called Isurium Brigantium (Aldborough near Ripon) This site has recently been the subject of a survey by Martin Millett and Rose Ferriby of Cambridge University. See also recent research and excavation at Faverdale ( 10 k west of Stanwick) , which has been suggested as the settlement developed by defeated Brigantians displaced by the fall of Stanwick.

So did the Brigantes rule a federation of smaller tribes across a large swathe of the north of the country?

The more likely scenario is that between AD 43 and AD 69 under Queen Cartimandua, the Brigantes were the largest tribal group in the area and they were recognised and their power bolstered by Rome partly for ease of administration, such as collection of taxes in slaves , hunting dogs etc. and partly as a buffer state against north Britain. When the tribe rebelled and the Queen was displaced Vespasian decided to conquer the whole area and impose direct rule.

As far as we can tell, nothing further was heard of the Brigantes throughout the Roman occupation.

There is at least one indirect reference in the Vindolanda writing tablets. Vindolanda was originally established as a fort on the Stanegate which linked present day Newcastle and Carlisle in the mid 80’s AD. Local inhabitants around the fort are referred to in one letter as “wretched little Brits”. As these people were almost certainly Brigantian the reference gives some idea of the way some Romans thought about the local people.

Research updated July 2017

Haselgrove, C. C . et al “Stanwick-Oppidum” Current Archaeology 119 1990c pp 380 -385

Ross, C. M. Tribal Territories from the Humber to the Tyne BAR British Series 540 2011

Proctor, J “ Roman Faverdale” Current Archaeology 273 Dec. 2012 pp 20-25

ART AND ARTIFACT

Welcome to Corner Cottage

Why not just take photographs? Visualisation and 3D imaging have transformed our methods of exploration. The camera records, stores, and simplifies so many useful facts in a exciting way. However investigation is not just about technique and technologies.

What the human eye can do is select and link subtle variations in shapes, textures, tones, colours, ideas and imagination in hundreds of different ways. Hand and eye used together have created highly detailed measured drawings, imaginative group and personal journeys and big screen cartoons. This has always been of great value to the archaeologist for recording, promoting and imagining.

By using both methods today it is now possible to obtain a more total interpretation of archaeology, or at least to try.

We should be aware of and use all these methods. Articles in the latest archaeology magazines certainly support this approach.

Useful and decorative materials did exist centuries before the Roman invasions, sometimes in large quantities, and there were good trade routes as far as India and possibly beyond. Travel could be very very slow if you were not on a main route. The latest thinking is that waterways and sea travel were used much more than we realised.

How or whether the materials were used, might have depended on the capacity to barter, the hierarchy of the group and the value of precious metals to reinforce status, and whether your tribe or society placed value on new technologies. Recycling then as now was a necessity for ideas, designs and technical innovations to develop.

My work explores landscapes and material culture including ‘small finds’

The small models are ‘thought provoking’ 3D material maps. Loosely based on archaeology methods, qualities of materials, and new technologies such as 3D mapping. Carefully researched, and sometimes humorous. Collages and models are for sale.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme was started in 1996 when the Treasury Act was passed which replaced the medieval law of ‘Treasure Trove’ in England and Wales, but not Scotland. PAS records ‘finds’ made by the public, including detectorists. Small archaeology items which might have been lost or removed from context are now recorded. It is based at the British Museum.

Kitchen

1 Froggatt Edge ancient tracks.

2 Sheffield. Autumn from Houndkirk Road.

3 Towards Robin Hood's Stride, Derbyshire.

4 Barbrook, Totley Moor- entry to the stone landscape.

5 Small oak, near Carl Wark.

6 Higger Tor, snowscape.

7 Carl Wark, hidden Hillfort

8 Combes Moss Hillfort near Buxton.

Sitting Room

9 Brigantes at Stanwick, North Yorkshire. Ramparts at dawn and dusk.

Examples of chariot gear, bits, terrets and linchpins for securing

Wheels. Bronze Horse Mask 10cms high, decoration from a wooden

bucket. It has characteristic Celtic features of lentoid eyes and

moustache. Hoard found at nearby Melsonby.

Studio

10 ‘Theatre of Fire’, furnace and some Romano-British brooches.

11 Lava fields Iceland 2014

12 ‘ the boar and the pony’. Work in progress, researching native British

coins.

13 Carnyx, Celtic war horn, an original head from Deskford, Scotland

Dated 75 AD- 200 AD. Section from the almost pure silver Gundestrup

Cauldron ( for ceremonial drinking), now in the National Museum of

Denmark, showing continental style Carnyx being blown in battle.

As with modern art today, designs would be made to be read from a

distance. The Carnyx had a movable jaw and red tongue which

vibrated when blown in a battle situation, and made a terrifying noise.

A special drinking vessel would be admired and envied for its

craftsmanship and symbolism, but would be seen in detail at very

close quarters.

14 Whirlow. Dig site 2016. Collage on Italian canvas using Japanese

papers and mixed media. (see sketchbook studies)

15 Some Romano- British brooches including the large Aesica type found

at Great Chesters, Hadrian’s Wall. Also type fabrics from the Iron Age,

such as Soay sheeps wool. Weaving techniques found at Hallstatt in

Austria, traces on bog bodies and artefacts.

16 Whirlow, ancient track, Fenney Lane.

17 ‘ Iron Age selfies’. At the British Museum Exhibition of Celtic Art, some

people were struggling to see details on cast finely engraved metal

faces, some less than 1 cm. Even with glasses and a provided lense.

One can only guess at the age of the metal craftsmen and women. Life

expectancy would be short. Perhaps this tells us more about the ages

the present day viewers! The examples are from handles on drinking

vessels and brooches. Humour is seen in the reverse faces on thin

sheet gold.

18 Examples of recycling from the Snettisham hoard found in Norfolk.

Finished pieces and metal blanks in various metals. Also revealed is

the structure of some of the larger torcs.

19 The Dinnington Torc. Found in Scratta Wood Iron Age Settlement near

Worksop, South Yorkshire. Restored and can be seen in Weston Park

Museum, Sheffield. This is a rare beaded type. Other examples are

another beaded torc from Lochar Moss and bronze collar from Stichill

both on the Scottish Borders.

20 The Dragonesque Brooch. Featuring some of the variations found in the

type, and enamelling.

21 ‘Minoan pin chain’ Crete.

22 Large stone with lichen. Bronze Age maps? St Agnes, Scilly Isles.

Models

1 Air movement

2 Earth, Bronze Age copper mining, Alderley Edge, Cheshire.

3 Crucible and fire.

4 Bronze forms.

5 Bronze animal. Carnyx.

6 Boundaries and tracks.

7 Iron Age beads. Recycling glass.

8 Snettisham. Recycling metal torcs.

9 Dragons’ nest. Dragonesque Brooch

10 Dragon shadows.

11 Trapped dragon.

12 Shrine offering, Roman site Nornour, Scilly Isles.

13 Leopard Brooch. Same site.

14 Amphora, wreck site off Sicily.

Welcome to Corner Cottage

Why not just take photographs? Visualisation and 3D imaging have transformed our methods of exploration. The camera records, stores, and simplifies so many useful facts in a exciting way. However investigation is not just about technique and technologies.

What the human eye can do is select and link subtle variations in shapes, textures, tones, colours, ideas and imagination in hundreds of different ways. Hand and eye used together have created highly detailed measured drawings, imaginative group and personal journeys and big screen cartoons. This has always been of great value to the archaeologist for recording, promoting and imagining.

By using both methods today it is now possible to obtain a more total interpretation of archaeology, or at least to try.

We should be aware of and use all these methods. Articles in the latest archaeology magazines certainly support this approach.

Useful and decorative materials did exist centuries before the Roman invasions, sometimes in large quantities, and there were good trade routes as far as India and possibly beyond. Travel could be very very slow if you were not on a main route. The latest thinking is that waterways and sea travel were used much more than we realised.

How or whether the materials were used, might have depended on the capacity to barter, the hierarchy of the group and the value of precious metals to reinforce status, and whether your tribe or society placed value on new technologies. Recycling then as now was a necessity for ideas, designs and technical innovations to develop.

My work explores landscapes and material culture including ‘small finds’

The small models are ‘thought provoking’ 3D material maps. Loosely based on archaeology methods, qualities of materials, and new technologies such as 3D mapping. Carefully researched, and sometimes humorous. Collages and models are for sale.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme was started in 1996 when the Treasury Act was passed which replaced the medieval law of ‘Treasure Trove’ in England and Wales, but not Scotland. PAS records ‘finds’ made by the public, including detectorists. Small archaeology items which might have been lost or removed from context are now recorded. It is based at the British Museum.

Kitchen

1 Froggatt Edge ancient tracks.

2 Sheffield. Autumn from Houndkirk Road.

3 Towards Robin Hood's Stride, Derbyshire.

4 Barbrook, Totley Moor- entry to the stone landscape.

5 Small oak, near Carl Wark.

6 Higger Tor, snowscape.

7 Carl Wark, hidden Hillfort

8 Combes Moss Hillfort near Buxton.

Sitting Room

9 Brigantes at Stanwick, North Yorkshire. Ramparts at dawn and dusk.

Examples of chariot gear, bits, terrets and linchpins for securing

Wheels. Bronze Horse Mask 10cms high, decoration from a wooden

bucket. It has characteristic Celtic features of lentoid eyes and

moustache. Hoard found at nearby Melsonby.

Studio

10 ‘Theatre of Fire’, furnace and some Romano-British brooches.

11 Lava fields Iceland 2014

12 ‘ the boar and the pony’. Work in progress, researching native British

coins.

13 Carnyx, Celtic war horn, an original head from Deskford, Scotland

Dated 75 AD- 200 AD. Section from the almost pure silver Gundestrup

Cauldron ( for ceremonial drinking), now in the National Museum of

Denmark, showing continental style Carnyx being blown in battle.

As with modern art today, designs would be made to be read from a

distance. The Carnyx had a movable jaw and red tongue which

vibrated when blown in a battle situation, and made a terrifying noise.

A special drinking vessel would be admired and envied for its

craftsmanship and symbolism, but would be seen in detail at very

close quarters.

14 Whirlow. Dig site 2016. Collage on Italian canvas using Japanese

papers and mixed media. (see sketchbook studies)

15 Some Romano- British brooches including the large Aesica type found

at Great Chesters, Hadrian’s Wall. Also type fabrics from the Iron Age,

such as Soay sheeps wool. Weaving techniques found at Hallstatt in

Austria, traces on bog bodies and artefacts.

16 Whirlow, ancient track, Fenney Lane.

17 ‘ Iron Age selfies’. At the British Museum Exhibition of Celtic Art, some

people were struggling to see details on cast finely engraved metal

faces, some less than 1 cm. Even with glasses and a provided lense.

One can only guess at the age of the metal craftsmen and women. Life

expectancy would be short. Perhaps this tells us more about the ages

the present day viewers! The examples are from handles on drinking

vessels and brooches. Humour is seen in the reverse faces on thin

sheet gold.

18 Examples of recycling from the Snettisham hoard found in Norfolk.

Finished pieces and metal blanks in various metals. Also revealed is

the structure of some of the larger torcs.

19 The Dinnington Torc. Found in Scratta Wood Iron Age Settlement near

Worksop, South Yorkshire. Restored and can be seen in Weston Park

Museum, Sheffield. This is a rare beaded type. Other examples are

another beaded torc from Lochar Moss and bronze collar from Stichill

both on the Scottish Borders.

20 The Dragonesque Brooch. Featuring some of the variations found in the

type, and enamelling.

21 ‘Minoan pin chain’ Crete.

22 Large stone with lichen. Bronze Age maps? St Agnes, Scilly Isles.

Models

1 Air movement

2 Earth, Bronze Age copper mining, Alderley Edge, Cheshire.

3 Crucible and fire.

4 Bronze forms.

5 Bronze animal. Carnyx.

6 Boundaries and tracks.

7 Iron Age beads. Recycling glass.

8 Snettisham. Recycling metal torcs.

9 Dragons’ nest. Dragonesque Brooch

10 Dragon shadows.

11 Trapped dragon.

12 Shrine offering, Roman site Nornour, Scilly Isles.

13 Leopard Brooch. Same site.

14 Amphora, wreck site off Sicily.

CRUCIBLES AND SPARKS

The Dragonesque Brooch.Unique to the north of Britain

The design develops the theme of the ‘broken back scroll’, popular on metalwork called La Tene from Switzerland.The designs were not directly Iron Age in form, but used old traditional decorative motifs. Visual references to sea horses, dragons, and dolphins.

All are motifs which create a definite rhythmic pattern, possibly connected to religious beliefs and mythology as well. These still have universal appeal. Such distinctive ‘old ideas’ in a new and highly visible design was clearly intended to make a statement about its wearer. A style of brooch work by the native people of northern Britain who may not have been in favour of the Roman presence. It is important to note that although a number of Dragonesque brooches held some form of significance, this does not mean that soldiers were in some way anti Roman. On fort sites this original traditional Celtic design would have been familiar to soldiers who came from other Celtic parts of the Empire, so they would have been acceptable to purchase or barter from the British in the local settlement by the fort or a market near to Roman main roads. Some very recent archaeology is being done on Dere Street where native and Roman building foundations are seen alongside.The artistic skills displayed on these brooches can be particularly helpful in defining different regional styles and identifying ‘schools’

70 different types of Dragonesque brooch were identified by R. W. Feacham in 1951, and more were found by 1968. They come mainly from native and military sites, caves and hoards. Most are enamelled in a small range of patterns and colours. Knowledge of enamel, glass and complex metal alloys may well have come via the Celtic tribes in Gaul. Ideas and materials could have travelled north from several directions by sea, river systems and as gifts between tribes. Both natives and Romans ‘borrowed, and developed a good design idea when they saw an opportunity! There are early native and later Roman Dragonesque brooches.

21st C viewpoints ‘ The big names hit the headlines’

Saxon hoards, Viking treasures, The Celts, labels, amazing technical skills, money, crowds. All have their place, but just sometimes the people, the hard working craftsmen and woman behind the glitter get lost. Processes were lengthy, skills acquired over generations, and often the artefacts were crafted in poor lighting. Where should we begin?

Brooches have always had a dual purpose since prehistory, being both practical and an identity statement. Not necessarily decorative, but displaying plenty of information. Clothes have always required fastenings to suit the fabrics available at the time. Through archaeology it is possible to trace a considerable amount of this early history, especially now with new technical equipment and methods available to analyse metal and craftsmanship. During the Bronze and Iron Age, early civilisations all across Europe, the Middle East and Asia designed and made amongst a mass of other metalwork, brooches ranging from very heavy masculine bronze fasteners 15-20cms across from coiled drawn wire, to the tiniest of 1 cm safety pins in other more precious metals, for the most delicate of woven fabrics. These look very modern. They tell us a lot about the people who wore them.

Rome did not have a monopoly on design and technology but their marketing and breadth of expansion across these areas did help the distribution of artefacts considerably. There is much activity by universities and amateurs going on at present to track these brooches. These ‘small finds’ are very well documented. There are hearths, moulds for casting, metal waste, recycling hoards of torcs and coins, and brooches themselves in various states of preservation.

CELTIC TWISTS

Much Celtic art is found on everyday objects such as jewellery, buckets, and drinking vessels, pottery, weapons and horse gear. These show a love of colour and sense of humour, especially in faces and animals on drinking vessels and pins.These designs embrace a system of ideas and beliefs of which we can only glimpse an understanding.

Although our technologies and time scales are very different, similar rhythmic lines, circles, mirror images and colours are present in their world and ours. Today all over the internet, the general public, scientists and astronomers search for information, look into nano worlds to repair our bodies, and explore distant galaxies. Different purposes but looking at mathematical pattern in nature and solving basic engineering problems.

Some of the first tentative and surprisingly skilled technological steps were made during the Bronze and Iron Age, experiments with minerals, fire, and mixing alloys of increasing complexity. Back breaking work. Trial and error over thousands of years, but people were asking questions and building on successes as today.

Looking at artifactual evidence from across the north of Britain as a whole, MacGregor comments that during the Bronze and early Iron Age periods there is little evidence for the presence of decorative metalwork, and highly decorative pieces are likely to have been brought in. There is some debate now that this could have come via the western sea routes as well as from Celtic homelands in Switzerland, Germany and Austria. New evidence is challenging preconceived ideas.

The sheer quantity of decorative metalwork produced in the north of Britain towards the end of this period, and into late Iron Age comes in startling contrast. Although there is a clear increase in the amount of decorative metalwork produced in the Roman period, it should be noted that it was popular during Late Iron Age, and cannot be tied to the Roman presence. MacGregor also argues that whilst native metalwork was certainly influenced by contact with incoming ideas and styles it was not produced ‘on commission’ for the Romans but was created by the native population for the native population.

More and more information about this interaction between Roman soldiers and the inhabitants of Britain is emerging through archaeology all the time. Shifts in archaeological focus since the 18th century make this a fascinating study. Discoveries made each decade being explained within that framework, sometimes ignoring evidence we now consider to be of great value at the expense of big personal viewpoints. However the thoroughness and time allowed for recording and writing up of evidence and exchange of ideas has laid an invaluable foundation for new technologies and the next generations. It is an ever expanding jigsaw.

The Dragonesque Brooch.Unique to the north of Britain

The design develops the theme of the ‘broken back scroll’, popular on metalwork called La Tene from Switzerland.The designs were not directly Iron Age in form, but used old traditional decorative motifs. Visual references to sea horses, dragons, and dolphins.

All are motifs which create a definite rhythmic pattern, possibly connected to religious beliefs and mythology as well. These still have universal appeal. Such distinctive ‘old ideas’ in a new and highly visible design was clearly intended to make a statement about its wearer. A style of brooch work by the native people of northern Britain who may not have been in favour of the Roman presence. It is important to note that although a number of Dragonesque brooches held some form of significance, this does not mean that soldiers were in some way anti Roman. On fort sites this original traditional Celtic design would have been familiar to soldiers who came from other Celtic parts of the Empire, so they would have been acceptable to purchase or barter from the British in the local settlement by the fort or a market near to Roman main roads. Some very recent archaeology is being done on Dere Street where native and Roman building foundations are seen alongside.The artistic skills displayed on these brooches can be particularly helpful in defining different regional styles and identifying ‘schools’

70 different types of Dragonesque brooch were identified by R. W. Feacham in 1951, and more were found by 1968. They come mainly from native and military sites, caves and hoards. Most are enamelled in a small range of patterns and colours. Knowledge of enamel, glass and complex metal alloys may well have come via the Celtic tribes in Gaul. Ideas and materials could have travelled north from several directions by sea, river systems and as gifts between tribes. Both natives and Romans ‘borrowed, and developed a good design idea when they saw an opportunity! There are early native and later Roman Dragonesque brooches.

21st C viewpoints ‘ The big names hit the headlines’

Saxon hoards, Viking treasures, The Celts, labels, amazing technical skills, money, crowds. All have their place, but just sometimes the people, the hard working craftsmen and woman behind the glitter get lost. Processes were lengthy, skills acquired over generations, and often the artefacts were crafted in poor lighting. Where should we begin?

Brooches have always had a dual purpose since prehistory, being both practical and an identity statement. Not necessarily decorative, but displaying plenty of information. Clothes have always required fastenings to suit the fabrics available at the time. Through archaeology it is possible to trace a considerable amount of this early history, especially now with new technical equipment and methods available to analyse metal and craftsmanship. During the Bronze and Iron Age, early civilisations all across Europe, the Middle East and Asia designed and made amongst a mass of other metalwork, brooches ranging from very heavy masculine bronze fasteners 15-20cms across from coiled drawn wire, to the tiniest of 1 cm safety pins in other more precious metals, for the most delicate of woven fabrics. These look very modern. They tell us a lot about the people who wore them.

Rome did not have a monopoly on design and technology but their marketing and breadth of expansion across these areas did help the distribution of artefacts considerably. There is much activity by universities and amateurs going on at present to track these brooches. These ‘small finds’ are very well documented. There are hearths, moulds for casting, metal waste, recycling hoards of torcs and coins, and brooches themselves in various states of preservation.

CELTIC TWISTS

Much Celtic art is found on everyday objects such as jewellery, buckets, and drinking vessels, pottery, weapons and horse gear. These show a love of colour and sense of humour, especially in faces and animals on drinking vessels and pins.These designs embrace a system of ideas and beliefs of which we can only glimpse an understanding.

Although our technologies and time scales are very different, similar rhythmic lines, circles, mirror images and colours are present in their world and ours. Today all over the internet, the general public, scientists and astronomers search for information, look into nano worlds to repair our bodies, and explore distant galaxies. Different purposes but looking at mathematical pattern in nature and solving basic engineering problems.

Some of the first tentative and surprisingly skilled technological steps were made during the Bronze and Iron Age, experiments with minerals, fire, and mixing alloys of increasing complexity. Back breaking work. Trial and error over thousands of years, but people were asking questions and building on successes as today.

Looking at artifactual evidence from across the north of Britain as a whole, MacGregor comments that during the Bronze and early Iron Age periods there is little evidence for the presence of decorative metalwork, and highly decorative pieces are likely to have been brought in. There is some debate now that this could have come via the western sea routes as well as from Celtic homelands in Switzerland, Germany and Austria. New evidence is challenging preconceived ideas.

The sheer quantity of decorative metalwork produced in the north of Britain towards the end of this period, and into late Iron Age comes in startling contrast. Although there is a clear increase in the amount of decorative metalwork produced in the Roman period, it should be noted that it was popular during Late Iron Age, and cannot be tied to the Roman presence. MacGregor also argues that whilst native metalwork was certainly influenced by contact with incoming ideas and styles it was not produced ‘on commission’ for the Romans but was created by the native population for the native population.

More and more information about this interaction between Roman soldiers and the inhabitants of Britain is emerging through archaeology all the time. Shifts in archaeological focus since the 18th century make this a fascinating study. Discoveries made each decade being explained within that framework, sometimes ignoring evidence we now consider to be of great value at the expense of big personal viewpoints. However the thoroughness and time allowed for recording and writing up of evidence and exchange of ideas has laid an invaluable foundation for new technologies and the next generations. It is an ever expanding jigsaw.

|

To download the Brigantes Display Handouts click on "download file"

|

| ||

| brigantes_art_and_artifact__1_.docx |

| brigantes_art_and_artifact__1_.docx |

See below the photos of the Brigantes Display held by Chris Rogers and the Brigantes Group